Dr Mary Gearey, Senior Research Fellow from the School of Environment and Technology at the University of Brighton and WetlandLIFE project partner reflects on her latest conference presentation and participation at AAG Washington 2019.

There seemed to be a problem on the streets of Washington DC when I arrived at the beginning of April. Dotted along the streets, scores of lonely, abandoned scooters, harshly left propped against streetlights, blossoming cherry trees, shop doorways.

Who would care for these miscreant mobile technologies?

Who would care for these miscreant mobile technologies?

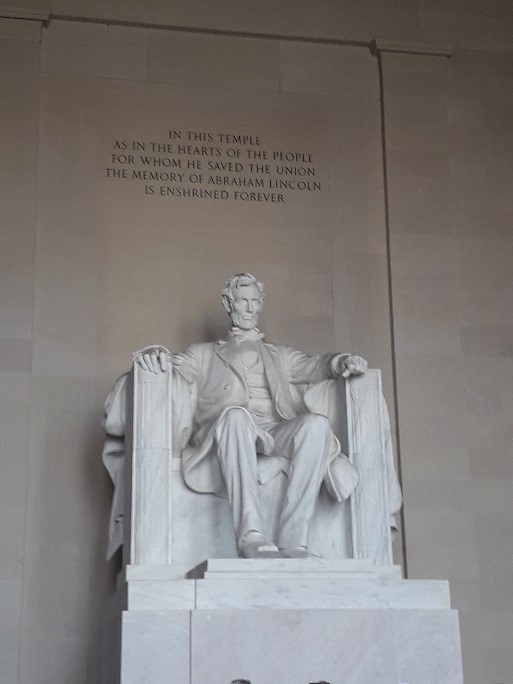

Luckily with 9000 physical and human geographers in town for the annual Association of American Geographers (AAG) meeting help was on hand with both theoretical and applied solutions. As it turned out, these smart scooters are a city wide endeavour to get both local residents, and tourists, out of their cars and buses to make the most of Washington’s relatively flat terrain. Sited in the valley of the Potomac river, central Washington’s topography is ideal for running, walking, cycling and scooting around – and many people make the most of the almost three mile walk between the iconic Capitol building and Lincoln Memorial, via the Washington Monument, to do just that.

Easy access extends to the civic amenities in Washington too. The Smithsonian Institution is a collection of several vast museums and art galleries, all free for public use: well, as long as there isn’t another US federal government shutdown as there was earlier in December 2018/January 2019 when all municipal buildings were closed due to President Trump’s suspension of funding legislation. The Smithsonian collection enables everyone to freely access a wealth of historic artefacts and cultural items of national importance. As a result this area of central Washington is humming with visitors from all countries and all parts of the USA. Visiting America’s capital seems to be an important life event for all junior high school children – and the streets are teeming with excited youngsters enjoying the somewhat Brutalist architecture of the Smithsonian collective.

So Washington was the perfect place to hold the AAG, the conference was last hosted by the city in 2010, with something to delight all the geographers present. This year’s rather subdued conference grappled with issues concerning economic and climate precarity and the damaging political-ecological impacts of agro-mining industrialisation, connective migration and social exclusion patterns; with Trump’s wall building programme casting a long shadow across the continent.

So Washington was the perfect place to hold the AAG, the conference was last hosted by the city in 2010, with something to delight all the geographers present. This year’s rather subdued conference grappled with issues concerning economic and climate precarity and the damaging political-ecological impacts of agro-mining industrialisation, connective migration and social exclusion patterns; with Trump’s wall building programme casting a long shadow across the continent.

Amidst the reflective moments there were opportunities to connect with old associates, meet new potential colleagues and learn about emerging and valuable research; including that from the University of Brighton itself, where I was presenting some initial empirical research findings from the WetlandLIFE project. The session I was participating in ‘geographies of the pluriverse’ was concerned with thinking around strategies to enable alternative ways of being-in-the-world to find a voice in society and in politics. Rather than one dominant way of understanding the world (such as the current framing of value equating with money in modern capitalism), a pluriverse approach embraces difference and considers ways of life that work in harmony with the planet. For example, some of the presenters discussed the importance of supporting indigenous scholars and activists in raising global awareness concerning environmental degradation as a result of mining or industrial scale non-native crop agriculture.

The link with WetlandLIFE’s work is the ways in which debates concerning environmental stewardship need to prompt us to connect with nature in many different ways, both to take care of our surroundings, and in turn to support our own health and wellbeing. This is at the heart of WetlandLIFE’s research. My presentation discussed the myriad ways that Specialist Interest Groups that utilise wetland spaces (such as birders, botanists, artists, educationalists, archaeologists) make use of these green-blue landscapes. I discussed how some users were drawn by specific animal or plant species, that others thought about wetlands over ‘deep time’ and see them as intrinsically connected to the surrounding topography and geology of the region, shaping economic and demographic patterns, and how for many they are important remembrance spaces, both for past loved ones and as spaces in which our human ancestors lived and worked. Understanding these different cosmologies of wetland use provides us with insights as to how we can all learn to enjoy and respect these watery landscapes for all aspects of our health and wellbeing; particularly when we might need to learn to rub (or scratch!) alongside our insect brethren as we adapt to a warmer, wetter climate in future days. It was a privilege to share our WetlandLIFE fieldwork with other global geographers and to see the resonance of our work with others operating in very different research areas.

The link with WetlandLIFE’s work is the ways in which debates concerning environmental stewardship need to prompt us to connect with nature in many different ways, both to take care of our surroundings, and in turn to support our own health and wellbeing. This is at the heart of WetlandLIFE’s research. My presentation discussed the myriad ways that Specialist Interest Groups that utilise wetland spaces (such as birders, botanists, artists, educationalists, archaeologists) make use of these green-blue landscapes. I discussed how some users were drawn by specific animal or plant species, that others thought about wetlands over ‘deep time’ and see them as intrinsically connected to the surrounding topography and geology of the region, shaping economic and demographic patterns, and how for many they are important remembrance spaces, both for past loved ones and as spaces in which our human ancestors lived and worked. Understanding these different cosmologies of wetland use provides us with insights as to how we can all learn to enjoy and respect these watery landscapes for all aspects of our health and wellbeing; particularly when we might need to learn to rub (or scratch!) alongside our insect brethren as we adapt to a warmer, wetter climate in future days. It was a privilege to share our WetlandLIFE fieldwork with other global geographers and to see the resonance of our work with others operating in very different research areas.

As our WetlandLIFE projects enters its final phase it’s been a privilege to share outcomes with global geographers at such a prestigious event as AAG. Though I never did muster the courage to ride a scooter with the downtown Washington traffic… maybe next time!